Keeping kids in school and not compromising

education.

VALUE OF VACCINATION

Education

When children aren’t vaccinated against childhood diseases, there are not only health implications. Even if the infection is not fatal, getting sick can mean they miss out on significant amounts of schooling or drop out altogether. This one event can have catastrophic consequences on their development, ability to gain employment and their wellbeing throughout life.

Keeping kids in school

Measles can cause visual and hearing impairment, which can mean that in areas without adequate provision for teaching kids with disabilities any child whose vision or hearing has been affected by measles will have to drop out. Vaccination against measles prevent symptoms such as loss of vision, neurological damage, middle ear infections (which can lead to hearing impairment thus affecting learning), and undernutrition.

In a rural community in South Africa, for every five to seven children vaccinated against measles by the age of one year, one additional school year was gained.

This was the case even for siblings who shared the same household and parents but were not both vaccinated against measles.

A 2019 study of around 2,000 children in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam has shown that when kids are vaccinated against measles at ages 6–18 months they do much better on a variety of school scores.

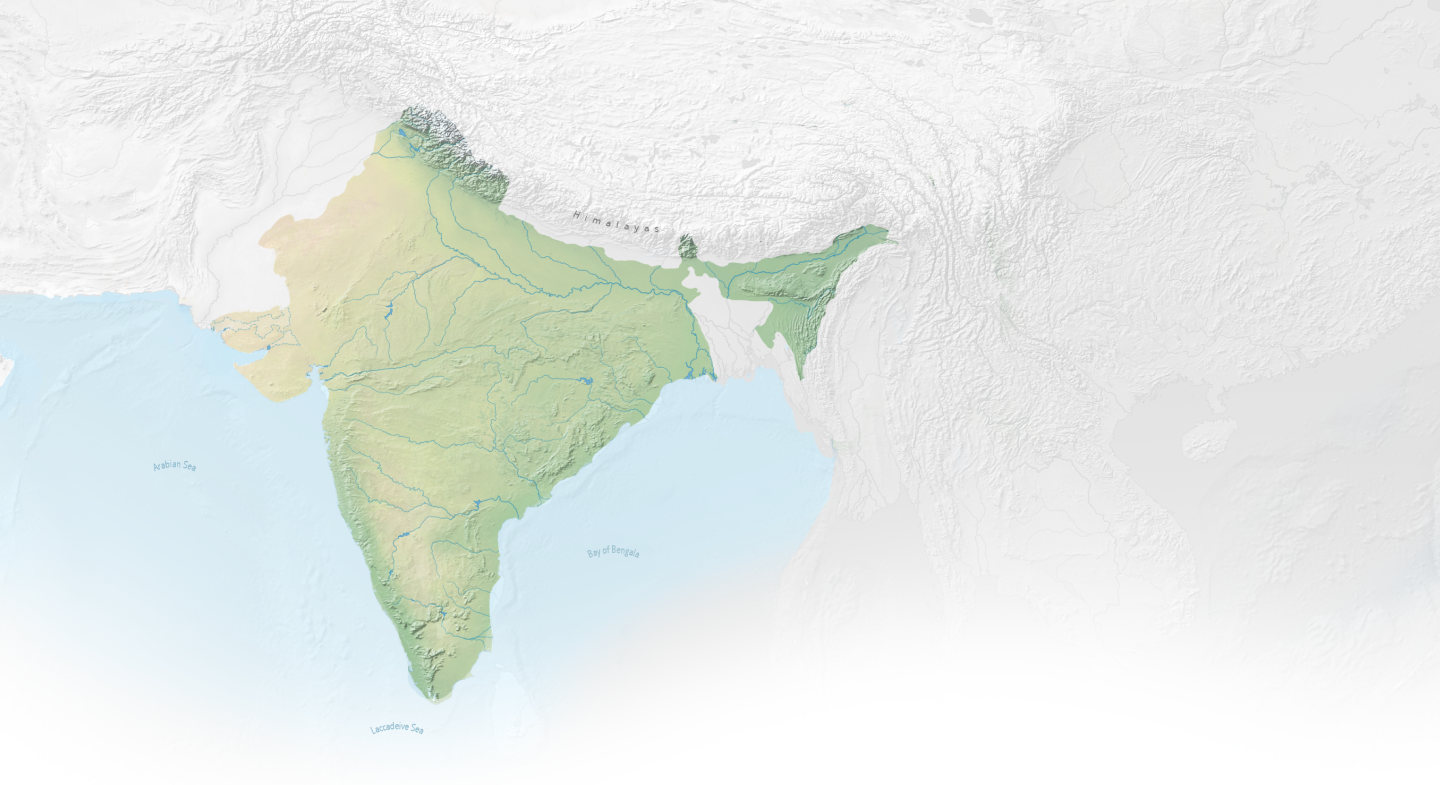

India's mission to immunise every child

India implemented the Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) in the 1980s to scale up the delivery of four childhood vaccines: one dose each of measles and BCG (against TB), three doses of polio vaccine and three doses of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccine, as well as tetanus shots for pregnant women.

This had a significant effect on reducing child deaths - between 1990 and 2015, the annual deaths among children under the age of five years fell from 3.4 million to 1.2 million in India.

A study of over 110,000 people in India looked at the effect this vaccination drive had on schooling. People who as children had been included in the UIP gained up to 0.3 more grades of schooling, as compared with those who were not in the programme.

Vaccinating pregnant mothers against tetanus has a major effect on child health and schooling

Maternal vaccination

Vaccinating pregnant mothers against tetanus has a major effect on child health and schooling because newborns make up a large proportion of tetanus cases – often because non-sterile equipment is used to cut the umbilical cord in childbirth.

In one study about 3% of children went from no schooling attainment to achieving 8 or more years of schooling if their mothers received the tetanus vaccination.

Nutrition and schooling

Vaccines can directly impact schooling through preventing infections that can affect learning or cause children to drop out of school. But there is also an important connection between immunisation and nutrition.

Undernutrition in children under five can cause general malaise, apathy and decreased physical activity. They may receive less interaction with adults and fewer learning opportunities, which can badly affect their cognitive and physical development.

Why vaccines are especially important for schoolgirls

Cervical cancer kills over 300,000 women every year. Protecting girls against cervical cancer is vitally important, especially in lower income countries - it is the number one cause of death from cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

The HPV vaccine that girls get around age 12-13 years protects against this killer disease. Although they may not develop cervical cancer until they are older, the vaccine prevents genital warts and cervical dysplasia (pre-cancerous cervical cells) that can happen while girls are at school.

Childhood vaccines ensure that girls stay in school, ideally until they receive their HPV vaccine - this is critical, because schools are an important access point for reaching teenage girls.

Out-of-school lessons learnt in Liberia

Giving ten-year-olds like Princess Ko the HPV vaccine is critical as it can protect her against cervical cancer, the leading cause of death from cancer in African women. As Princess lives too far from a school to attend it, she missed out on school programmes and relied on mobile immunisation teams for her vaccine. Liberia is using HPV vaccination as a platform to roll out broader adolescent health and education interventions, such as nutrition, body literacy and menstrual hygiene.

The social impact of vaccination on gender equity is significant in keeping girls in school and ensuring they complete their education. And even when boys in the family get sick, teenage girls are often expected to stay home from school and look after their younger brothers - ultimately girls are the ones most likely to see their schooling affected.

Ensuring that girls stay in school is especially important as it reduces their changes of being married off as children, which significantly impacts their health and wellbeing for life, especially as they may themselves then give birth too young. This means they are less likely to die in childbirth.

Preventing cervical cancer also has developmental effects. It perpetuates the cycle of poverty because it affects the young, working-age women who are often the head of the household, economic contributors, and caregivers, which increases the household risk of financial hardship. Aside from losing income when cervical cancer strikes, families have to sell their farms and basic property to access treatment.

Cyclical benefits of education

Investing in vaccines to ensure that children get education also has a cyclical effect in boosting vaccination rates in the future. The more that both parents understand the importance of vaccines in disease prevention, the more likely they are to ensure that their kids are vaccinated. In Nigeria, 94% of children with illiterate mothers do not receive full immunisation. Educated mothers in Gambia, West Africa, are more than twice as likely as non-educated mothers to get their children vaccinated. Mothers who are educated are also more likely to educate their own children, again perpetuating a positive cycle.